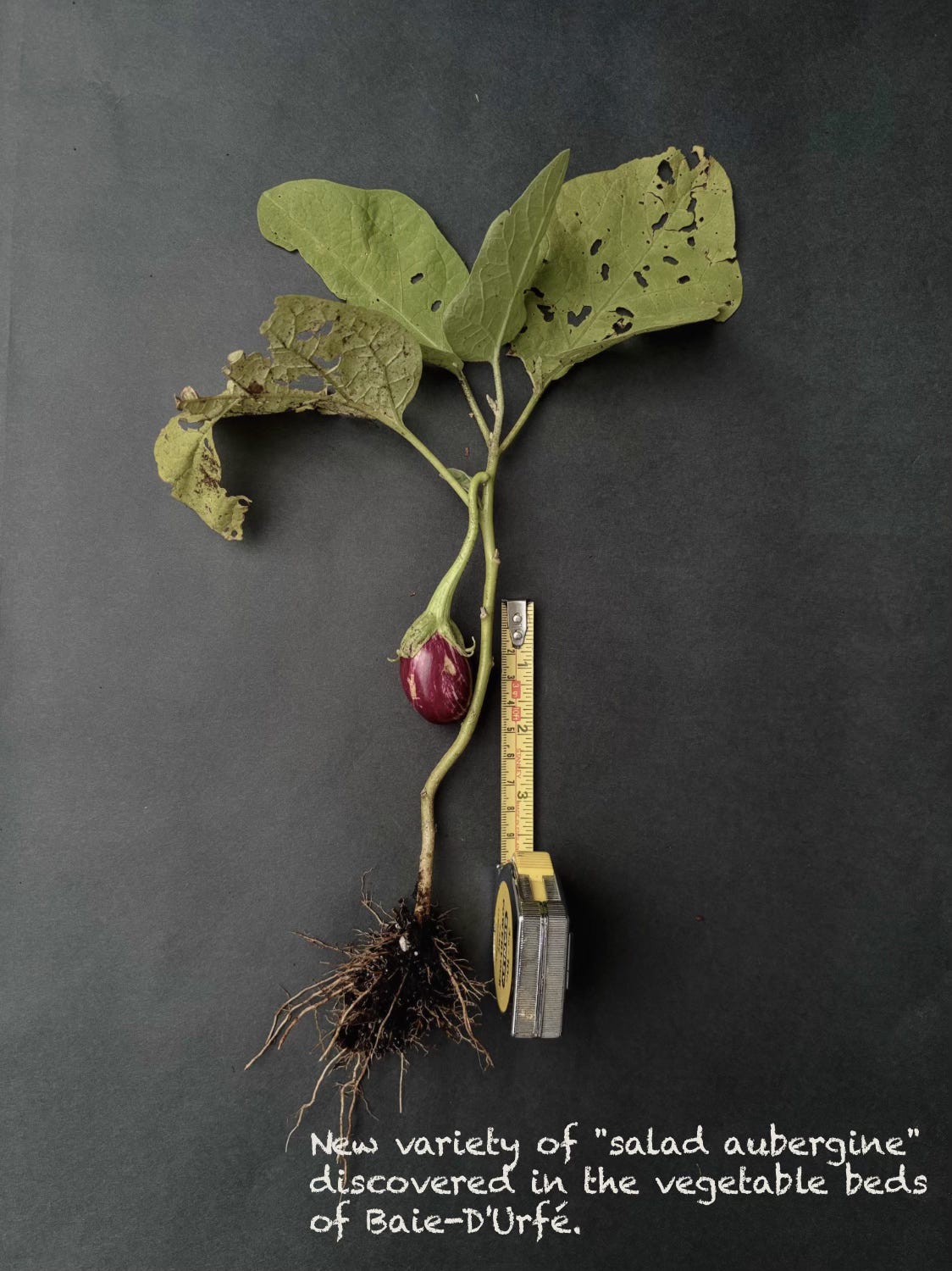

When we first came to live in Canada one of the first things we had to contend with was that seasons do not morph one into another but seemed to change almost overnight … and that spring only lasts a fortnight with all the seasonal flowers apparently blooming together before that flips into a too hot summer, but that’s another story. Now we have climate change at work and this September, instead of comfortable low-twenties temperatures and a sufficiency of rain we have had several weeks of “July” climate with no rain and at one point temperatures approaching 30C. Rather disorienting. This week normal service has more or less been resumed … and some rain too so the ground is softening and we can begin to catch up on the fall speciality of moving plants around.

It’s been a wonderful year for fruits and berries of all sorts. Birds that were planning to migrate south and party until spring have pretty well all gone now, just leaving the old faithfuls to entertain us in the cooler and cold months ahead. Resident creatures are frantically piling on extra layers of fat to see them through the lean times. This pair of opportunists for example … admittedly the pumpkin is from last year but I thought you’d enjoy the picture.

As October approaches, our garden is still actively buzzing with insects - helped along by the abnormal warmth of the past few weeks. Especially popular with us are all the drifts of blue wood asters that have now come into their own. (Quote - J.E. Fishman): “In addition to beautifying the early fall landscape, wood asters play an important role in the local ecology. According to the National Wildlife Federation, 115 species (which is to say many species depending on where you live) of butterflies and moths use asters as a host plant”.

It’s a nice time of the year as we really have little to do in the garden that is really urgent - other than scooping falling leaves out of the pond - and so we can sit back and enjoy whatever is happening. That’s the theory. In practice we have begun to eye up specific plants and muse “wouldn’t that look better over there, next year” which means that that plant is going to be moved. Gardening is always a work in progress, and long may it be so.

Not every species seen by chance is a beauty, sometimes they are merely a curiosity. This tiny creature appeared on a window blind … for the record it is a Common Eupithecia Moth (Eupithecia miserulata) and it really isn’t famous for anything particular. Its larvae have catholic tastes and will happily live on a majority of the native plants we have in the garden.

Keeping Records

I was going through our personal records of confirmed species seen anywhere within the boundaries of Baie-D’Urfé. Our town does not occupy a huge area, just 6 sq.km, or a bit less than 2.5 sq.miles but nevertheless, there is enough space to offer homes to many more species than most residents would suspect - almost exactly 400 species in all plus all those we don’t have a record of yet. Here is a tally of the ones that we have personally confirmed and made a note of.

Plants 144, Birds 135, Insects 81, Arachnids 13, Fungi 11, Mammals 10, Molluscs 2, Amphibians 2 (American Toad, Green Frog), Reptiles 1 (Northern Map Turtle)

There is nothing magical or particularly hard about keeping accurate records of species seen in a particular location, but it is interesting and fun. Taxonomy - that’s the science of naming and describing species and fitting them into the “tree of life” as it were - is an arcane field and most practitioners will be the first to tell you they they only really “know” about their own specialist and often tiny field of interest. Being a biologist certainly helps me to know what I don’t know, and anyway taxonomy was far from my particular area of expertise, but mostly it just means I usually know where to look for the required information - which is half the battle in putting a name to something that interests you. When people ask, as they do, the safe response is almost always “I don’t know, but I’ll look it up”.

In other words, if birds or flowers or spiders or whatever are something you find interesting then you can learn about them too without having to have a string of letters after your name. Recording what and where you found any species of particular interest is actually immensely important to building the information needed to protect them. All the more so in these days of climate change and habitat loss. All the specialist biologists in the world cannot gather the breadth of data that is needed - but citizen scientists like you can contribute and help. There are internet tools available to report your observations where the scientists who study populations can find them and I urge everyone to use them. A few, have surprisingly accurate artificial intelligence facilities built in that will assist you in putting a name to what you see. They are not always infallible, but they will usually narrow the field down enough for you to work out the rest for yourself. If the worst comes to the worst then send me a photo and some information where you saw it and I will gladly do what I can to find a name for you. One of the biggest promoters of Citizen Science is the Cornell University Lab. of Ornithology who sum up the important contribitions we can bring, as follows:

Hundreds of thousands of people around the world contribute bird observations to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology each year, gathering data on a scale once unimaginable. Scientists use these data to reveal how birds are affected by habitat loss, pollution, disease, climate, and other environmental changes. YOUR participation will help us trace bird migration, nesting success, and changes in bird numbers through time. These insights inform conservation plans and key actions to protect birds and habitats.

Don’t disturb wildlife … be careful

A rather important article in the press this week … it applies wherever you happening to be reading this.

A new paper in the Science of The Total Environment journal has highlighted the negative impacts of online posting and photography on biodiversity. By calling attention to rare flora and fauna – and in some cases their precise locations – nature enthusiasts posting about finds can cause others to flock to the same location, and even to deploy unethical tactics (such as playing back bird calls or using bait) to secure a sighting for themselves.

A splendid book for wildlifers who garden …

I’d like to draw to your attention a splendid book that will be of interest the everyone who enjoys wildlife/natural gardening. This is a book that I have been reading recently and really, it says so many good things in a most readable way. The title is “One Garden Against the World: in search of hope in a changing climate” by a British author, Kate Bradbury, who writes on such topics for the BBC, the Guardian newspaper, and appears on various television shows. So she knows her stuff. One reviewer (Melissa Harrison, a Substack writer and author of books whom I highly commend) says it is “ … an invitation to a deeper relationship with the world around us, and proof of what might be achieved if we become true custodians of our nearby nature”.

Starting with a quotation, that for me sums up neatly why we (J and I anyway) do the wildlife garden thing.

Where are they? Why aren't they in my wildlife garden? I'm surrounded by concrete but some of us are growing flowers. Is it enough? Will there ever be enough? I garden for the wild things, for my sanity, for the child with her head in the thatch. I want there to be more wildlife. I want swifts in my nest boxes, butterflies on my buddleia. I want ants and slow worms and earwigs and caterpillars. I want fat hedgehogs that are fat on beetles, not cat biscuits. I want a full clutch of tits in the tit box. I want abundance and noise and to stop worrying about every last quiet thing. Is that too much to ask?

This book is a call to arms to gardeners, communities and individuals, to do more for wildlife and the climate. Climate change and biodiversity loss go hand in hand, but if we work together, it's not too late to make a difference. The places that we can make a difference are the ones in which we can get our hands dirty. Facebook likes do little in reality but if we have a garden, however small - and author’s is small - then what grows, lives, feeds there is very much dependent on us to ensure that it thrives. Kate Bradbury tends a small garden in a terraced house. In an increasingly urban environment, she endeavours to not only create a haven for our rapidly disappearing wildlife – the insects, bees and butterflies, hedgehogs, frogs and wild birds – but to persuade us to do the same. It’s a well researched read, part horticultural and part memoir, that takes you through the months and discusses the benefits that wildlife gardening brings … hedgehogs and Gulls have starring appearances. In particular is the emphasis on the aggregate importance of hundreds of thousands, millions even, of small urban and suburban gardens as a major resource for species that are declining in population.

At the end of the book she says this … I find it rather appealing.

When I'm old I will sit at the window and look at the garden, with tea, and I will watch my world grow wilder without me. There's no shame in letting your garden go as you age. There's no harm in setting it free. There's a beauty, I think, in watching your patch of land grow as you fade. My garden is wild enough as it is but I am always in it, with secateurs and twine, tying bits in, trimming, controlling. The frivolity and freedoms of youth, long gone for me, will be realised outside, in one final, out-of-control party. What new species will turn up? Who will make nests? I am almost looking forward to it. I will hobble out to top up bird baths.

Shocking

I chanced upon a “lifestyle” website that gave instructions for ridding your garden ground-nesting solitary bees. As if they weren’t struggling enough to find somewhere to breed. Hard to understand - having a small colony is something to be desired, encouraged, applauded. We have such a colony and you’d hardly know they were there unless you go looking - they are certainly no threat to anyone. What is worse than one aberrant website like this, is that when I googled the topic I unleashed a positive flood of similar articles and instructions about how to kill them. What is the matter with people?

Here’s an instructive cartoon for a bit of fun - this is a genuine bird and not an illustrator’s fantasy … enjoy, the Night Parrot of Australia

I am all for more wildlife in my small patch of garden in urban Toronto; and I am doing my part to keep it as wild & welcoming as possible to all manner of feathered and furry beings and all of the insects necessary to biodiversity. And beauty, of course.

"What is the matter with people?". Indeed. I speculate we are speciating into two groups

H. Urbanis and everybody else. The former group finds it a bother to deal with anything other than client species so they sort things out by reaching for the pesticide.