At this time of year in later summer, we often see – and yes, some of us enjoy – the appearance of large spiders in our gardens. Large yellow and black spiders sitting in the middle of a big web with a “zipper” feature. Really hard to miss sometimes. You could go out today and find some, I am certain … or send the kids on safari.

Today’s relevant quotation (found on Quora, author unknown):

Spiders occupy a completely alien world that’s literally right under our noses. Anything you find out about spiders, from where they live to how they mate to how their bodies work, is bound to be astounding. Most people have surrounded themselves so thoroughly with ignorance and fear that they’re nowhere close to appreciating what marvels these small creatures are. And once you start seeing them as objects of endless interest, the excessive fear goes away. It really does—I’ve seen it in so many people.

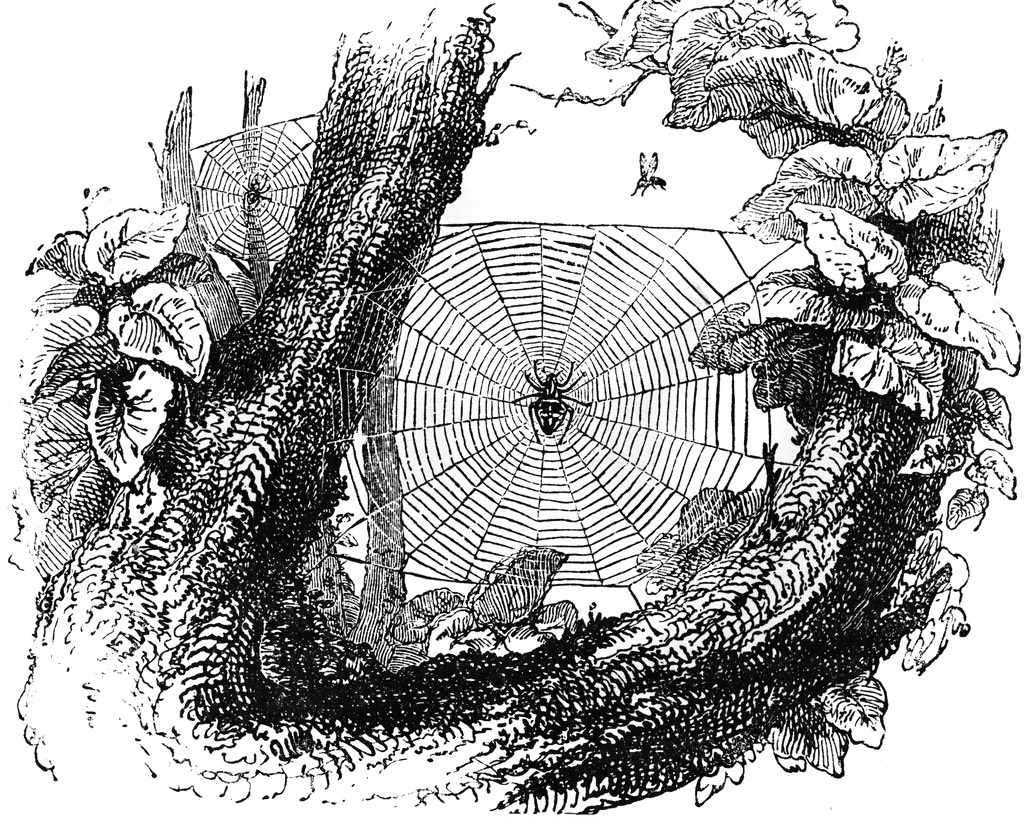

This post focuses on three species of the group known as Orb Web Spiders that are commonly seen at around this time of the year when they have grown enough to be hard to miss. The commonest around here is the not very imaginatively named Yellow Garden Spider (Argiope aurantia) which almost glows in the dark, it is so strikingly marked. Just occasionally I see specimens of the related Banded Garden Spider (Argiope trifasciata). Another one you should be able to find, though rather more subtly coloured, is the Cross Orbweaver (Araneus diadematus) which is a non-native spider that arrived from Europe and settled here long ago. These are big fellows for the most part and it is worth spending some time carefully combing through the grasses and leafy border plants searching for them. There is a high chance of finding them in your garden if it is not entirely composed of mown lawn.

Yellow Garden Spider

Yellow garden spiders often build webs in areas adjacent to open sunny fields where they stay concealed and protected from the wind. The spider can also be found along the eaves of houses and outbuildings or in any tall vegetation where they can securely stretch a web. Females tend to be somewhat local, regularly staying in one place throughout much of their lifetime.

Banded Garden Spider

Like the Yellow Garden Spider, the young of these spiders hatch in early summer but do not become readily visible until mid-August, when they have grown large enough to make their distinctive webs. To counter the arrival of European Cross Orbweavers on our shores, members of this species have travelled the other way and are enjoying a life in Europe, especially in Spain. They are rounder, and a bit larger than the YGS. The specimen I photographed below had been in place for over a week in a patch of bush beans in a vegetable patch. The beans were picked carefully around the spider so as not cause disturbance. It increased markedly in size over that period - obviously lots of nutritious snacks came her way, possibly including a male, because that’s what these spiders do.

Cross Orbweaver

The colours of individual spiders vary from light yellow to dark grey with some around here at least being assorted shades of pink. They all have mottled white markings across the dorsal abdomen forming the shape of a cross.

Web spinning

Wikipedia describes the process quite succinctly:

To construct the web, several radial lines are stretched among four or five anchor points that can be more than three feet apart. The radial lines meet at a central point. The spider makes a frame with numerous more radial lines and then fills the centre with a spiral of silk, leaving a 7.9–9.5 mm gap between the spiral rings, starting with the innermost ring and moving outward in a clockwise motion. To ensure that the web is taut, the spider bends the radial lines slightly together while applying the silk spiral. The female builds a substantially larger web than the male's small zigzag web, often found nearby. The spider occupies the centre of the web, usually facing straight down, waiting for prey to become ensnared in it. If disturbed by a possible predator, she may drop from the web and hide on the ground nearby. The web normally remains in one location for the entire summer, but spiders can change locations typically early in the season, perhaps to find better protection or better hunting.

Stabilimentum

The Yellow and Banded Garden Spiders ornament their webs with a visually prominent zigzag feature called a stabilimentum. It was originally thought that this was a device to tighten and stabilize the web, hence its name, but that has now been disproved. It is noted however that stabilimentum-building spiders are largely diurnal and one suggestion is thus that this feature may offer protection to the spider as camouflage by breaking up its outline, or making it appear larger by extending its outline). Another, more recent, hypothesis is that the stabilimentum makes the web more visible so that birds are less likely to damage the spider's web. This is quite likely – even though food capture is demonstrably reduced by their presence and there is a high-energy cost to building a stabilimentum, so the benefit must be equally large. Finally, another hypothesis is that web decorations attract prey by reflecting ultraviolet light.

… and to top off the wonders, something you can take to the pub quiz night:

There are some orb-web spider species that don’t actually trouble to spin a web at all, but instead go fishing for their prey. The nearest of these to us are to be found in Central America and are commonly known as Bolas Spiders. They hunt by applying sticky "capture blobs" on the end of a silk line(the bolas), which they dangle temptingly. This sticky blob contains a synthetic pheromone that attracts males of certain moth species. By swinging the bolas at flying male moths, the spider can snag its prey, rather like a fisherman hooking a fish. They then reel in their next meal.

Spiders – you have to love them. At least, I hope you do, as there will probably be more spider posts in the months ahead. Some with gruesome habits, but all of considerable interest.

BONUS

KNOWING THE NAMES OF THINGS

This is rather a hobbyhorse of mine

“ … Not everyone can spend time in the (wilderness with professional biologists), but everyone can learn the names of the trees in a nearby park. Can you identify the birds calling in your backyard? Do you know the difference between a moth and a butterfly, or between a worm and a grub? Take the time to engage with both the little and big things growing around you and discover the joy of re-connecting with nature.

https://theconversation.com/identification-of-animals-and-plants-is-an-essential-skill-set-55450”

It’s fair to assume that if you are reading this newsletter, then you are already interested in and care about our wildlife and natural spaces. Welcome to the world of 1001 Species … however, judging by the number of “What is this?” posts on social media and questions put to me directly, it is evident that many people struggle to identify the wildlife and plants that they encounter. For most, it is simply a lack of opportunity to learn or not knowing where to find the information.

I fervently believe that knowing names is so very important. The names of plants and animals can spark curiosity and a desire to learn more. Starting with a name, we can venture as far as we feel comfortable into the complexities of biology, ecology, and environmental science. With knowledge comes understanding. It is undoubtedly a fact that those who can identify the one bird or flower from another similar one are more likely to engage in conservation efforts, will advocate for the preservation of habitats and vulnerable species that might otherwise be overlooked. I have certainly found that once you can help someone put a name to a creature that has caught their eye, they start to ask more questions – why is it here, what does it eat, is it poisonous, will it attack me and so on. A name is often a trigger to aid people in learning about and caring for our environment.

Naming is the first step in understanding and ultimately wanting to advocate for change that benefits our lives as well as those of the once common butterfly that we realise we haven’t seen this year. Canaries in the coal mine.

Carrying a notebook helps a lot too. Keeping records matters.

“Knowing the names of things is useful if you want to talk to somebody else – so you can tell them what you’re talking about.”

- Richard Feynman

If you have any thoughts on what you read here, I would love to hear from you. Positive or negative. I invite you to comment on the posts (and ‘like’, if you do indeed like) or, if already a subscriber, just reply to any of the emails you receive.

Your garden and its spiders are splendid! You must enjoy writing, but thank you for sharing.