Bugs (Hemiptera)

All bugs are insects but not all insects are bugs. It has become common for insects in general to lumped under the all encompassing category of bugs - wrong. Please call them insects. Except, of course, when they are bugs.

This quotation, see the link at the foot of the page, explains:

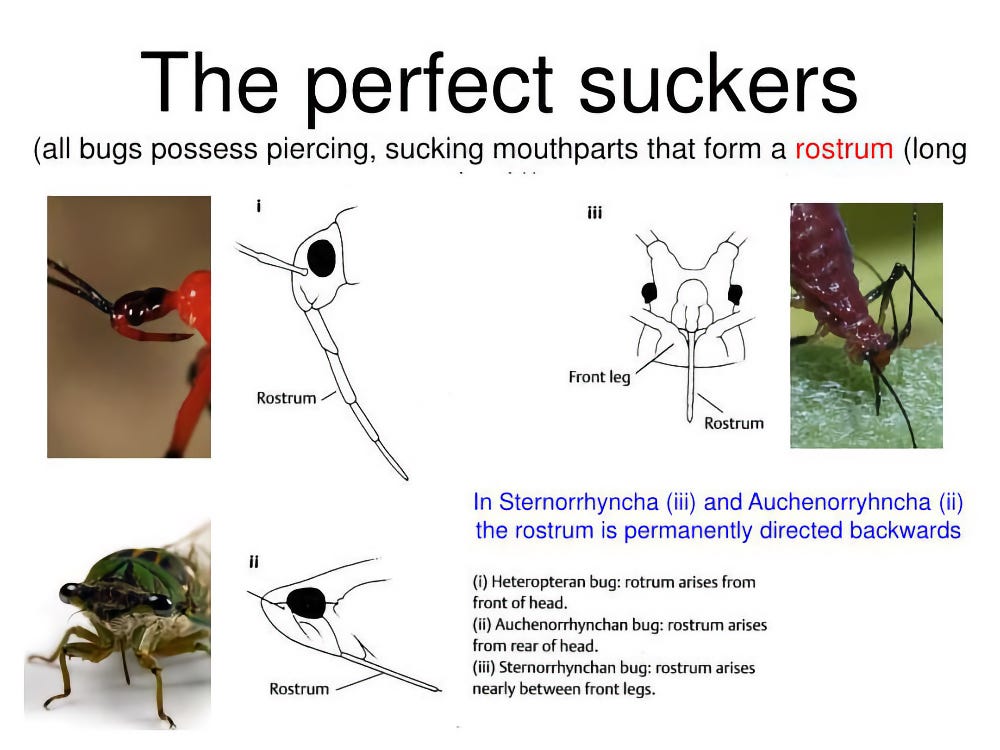

In popular culture, of course, a ‘bug’ is any sort of insect, but among entomologists, the term generally refers to the order Hemiptera, and particularly its largest subgroup Heteroptera. The word itself is a medieval English term, originally a general term for ‘something scary’ (think ‘boogeyman’ or ‘bogey’) which was first applied to insects, in reference to the bedbug, sometime in the early modern period. The defining feature of the Hemiptera is the structure of their mouthparts, which are adapted for piercing and sucking- a combined syringe and straw. Insects have two pairs of jaws, the mandibles and maxillae; in bugs, both have been elongated into hair-thin threads encased in a tubular beak. By ‘zipping’ the left and right pairs together, a tube is formed for sucking up liquid. The outer pair is needle sharp, which allows the bug to drill into plant tissue or pierce the cuticle of another insect.

So now you know … the term “bugs” has more and more come to be used for any small creature, be it an insect or spider. That is WRONG and causes confusion.

If you have read this far you will be amenable to my constant plea to please reserve the word bug for members of the Hemipterae, which are distinguished from other insect groups by having sucking and not chewing mouthparts. Most of the many species feed on plant sap while some feed on animal sources, such as the hemolymph of other arthropods and the blood of mammals (think bed bugs) and birds. The group includes cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, shield bugs, assassin bugs and bed bugs. As you can see, they are a diverse collection. Some are agricultural pests, the Aphids for example, while other species do good work such as controlling mosquitoes during their aquatic larval stage.

The Hemipteran mouthpart has been described as being “a marvel of evolutionary engineering: a compact, modular system that transforms a rigid set of chewing jaws into a delicate syringe capable of extracting nutrients from a wide range of sources”.

So, bugs inject saliva containing enzymes that pre‑digest plant cells and often contain compounds that suppress plant defenses. In predatory or blood‑feeding species, the saliva may contain anticoagulants or toxins that immobilize prey. After the saliva has softened the target tissue, the bug draws the liquefied material up through the food canal with muscular contractions of the head and thorax.

There are three sub-groups of true bugs:

Plant‑feeding bugs (e.g., aphids, cicadas, leafhoppers) that mainly ingest plant sap. Their saliva dissolves plant cell walls and counteracts plant defensive chemicals.

Predatory bugs (e.g., assassin bugs, reduviids) - these lovely insects inject neurotoxins and digestive enzymes that liquefy the prey’s tissues, allowing the predator to sip the pre‑digested body fluids. There’s a pleasant thought.

Blood‑feeding bugs (e.g., bedbugs, kissing bugs) with have especially potent anticoagulant and anesthetic components in their saliva to keep the host’s blood flowing and to avoid detection.

Around my part of the world we play host to a wide range of true bug species. One of the most prominent being Anasa tristis, the Squash Bug. If you grow squash plants in your garden you may well be acquainted with those particular fellows. The volunteers at the Garden at Fritz who I work beside, most certainly have been only too familiar with these fellows in past years before they found non-chemical ways to limit their activities.

Others you might see include various species of Stink Bugs and, really hard to miss, the Dog-day and Northern Dog-day Cicadas of late summer. If you are keeping a corner of your garden to grow milkweeds for the Monarch butterflies then look out for the Small, Eastern Small and the Large Milkweed Bugs.

Amongst the fascinating range of True Bugs here, and very much at the extreme northern edge of its range, which is to say they are rare, is the Insidious Flower Bug (Orius insidiosus), a name which I find especially appealing and so include it here. It is a useful devourer of small agricultural pests, especially Thrips, and is bred and released further south of us a biological control insect.

By the way … if, by now, you have had enough of weekly insect biographies (I can’t imagine why) know that you have only three more weeks to suffer through before I move on to plants. Well, I think plants but now’s the time to comment or email and persuade me to do fluffy bunnies or birds or spiders or whatever. You might change my mind, but something for the botanistically inclined would be a good thing.

Organisational note: … these short Noticing Nature posts appear once a week and if they interest you then at some point you may want to refer back to a specific species group already dealt with. To find them, click the link in the top menu bar of any post and you will see the Noticing Nature sections in chronological order as shown below.

Reference article - a good read:

I'm always fascinated by how pretty some of the bugs are. So many of them have lovely intricate markings.

Ironically the UK conservation charity for invertebrates is called Buglife. (https://www.buglife.org.uk/)

We love all insects, of all shapes and sizes. Every one is important!! Particularly if they are in their native habitat.