The Bee Edition

Starting to recognize easy Bumble Bees in your garden

Bees. Pretty well everyone likes bees, even though for most people when bees are mentioned they think of Apis mellifera, the European hive or honey bee. They will undoubtedly be aware of Bumble Bees (“What? You mean there are more than one species?) but more often than not, that’s where it stops. The hundreds and hundreds of species of social and solitary bees are a closed book to most. Just more bugs that “don’t look like bees” … to the extent that they happen to have black and yellow markings then they are clearly small wasps to be swatted. It’s not a lack of care so much as lack of education and not looking critically at what is around as we scuttle from one busy-busy place to another.

Now that summer, warmer weather and increased insect activity has arrived with the beginning of June I thought to write about the big, furry bees. The Bumble Bees … and where better to start than the ones in my own suburban garden and probably yours too. Garden bees, because they are right there outside our homes to look for and at. Anyone can see them.

Bumble Bees in my Garden

Lord, how hard bumblebees are to identify. Pretty simple to determine that we have a Bombus sp, but which one? Much time can be spent sweating over these; is it Two-spotted Bumblebee (Bombus bimaculatus) or is it the Half-black Bumblebee (Bombus vagans)? Or what? Is it one of the species on the decline, or one instead that is very stable in terms of population. Bumble bees are important insects that are abundant pollinators and which forage at a variety of plants.

Bumble bees live in underground nests, often in or around wooded areas and in quiet corners of gardens. Nests can be anywhere from 6 inches to a couple of feet below the surface. Tunnels traveling to the nest range from 9 inches to 4 feet long. These bees fit in between the hundreds of species of solitary bees on the one hand, and Honey Bees which live in hive-colonies of many hundreds or thousands of individual insects. Bumble Bees are not solitary, but “eusocial” in that they live in related social colonies of up to 250 individuals. The queen is the only one that overwinters, to emerge in the spring and start seeking a nesting site which it will stock with pollen and nectar on which she lays a mass of eggs that develop into adult workers after about a month. They then go and collect more pollen and nectar while the queen lays more eggs. At the end of summer she will lay eggs that supply males and some more new queens. Mating ensues outside the nest (genetic mixing with bees from other nests) The males then die and the mated queens go off to find a safe place to overwinter. Repeat ad infinitum down the millennia.

I have picked out four species of Bumble Bee species that have been seen in our wildlife garden (pictures are my own) and which I offer as starters along your path to becoming a bee aficionado or Melittologist. Have you got any of these? Or their relatives? Wherever you live, there will equivalent BB species to have fun with.

The Common Eastern Bumble Bee (Bombus impatiens) is, well, common. A very important pollinator species able to live in a wide variety of habitats. Here in Quebec we are at the northern range limit but there are a to of them around, if our garden is anything to go by. The thorax is almost all yellow.

The Two-spotted Bumble Bee (Bombus bimaculatus) A common bee that has been experiencing steady growth unlike many other bumble bees that are in decline. With long thoracic har and usually with two spots, or a W shape to be seen.

The Tricoloured Bumble Bee - also know as the Orange Belted BB (Bombus ternarius). Forages on Rubus, goldenrods, Vaccinium, and milkweeds of which we have plenty though this species only visits occasionally. Their range is more northern than the two preceding bees and present in both eastern and western Canada. Face is yellow; Thorax yellow with black band between the wing bases and a triangular wedge pointed towards the tail

Lastly, the Brown-belted Bumble Bee (Bombus griseocollis). Identifies with a brown belt on the anterior abdomen below the yellow hair. Can be found in many habitats, including meadows, wetlands, agricultural fields, and urban areas, even densely populated cities. They have even been seen near the top of the Empire State Building over 100 stories above ground level … can’t imagine they will find much pollen up there!

I guess the Tricoloured BB is easily distinguished, but the others? A bit more tricky. Try to get a detailed photo (some tips are in the link that follows) to help identification at leisure if you can … and remember, Bumble Bees are not at all aggressive and will usually let you get quite close.

https://iso.500px.com/a-bugs-life-the-essential-guide-for-photographing-insects/

If you are going to take an interest in bees, then it’s rather like becoming a birder. Don’t be overwhelmed but start local with just a few species. Get their identifications under your belt and move slowly outwards from there. This website should help: https://www.bumblebeewatch.org/field-guide/

Helping bees to thrive

We are all agreed that a world without pollinator species would be a hard world to live in, and lot less interesting. This, in fact, is one of the drivers behind the whole native plant/wildlife/pollinator garden movement. Indeed replacing alien garden plants with native ones is hugely important because, after all, all that pollination is done in exchange for our gardens providing nectar and pollen to insects. especially bees.

BUT … eating pollen and drinking nectar is only one half of what a pollinator insect needs to survive. Bees have to be able to reproduce and here is where things get more difficult. Bees need suitable nesting habitat and that is becoming more and more scarce in a world being rapidly paved over by roads and parking lots and houses and driveways and patios and garden swimming pools. Almost all bee species are underground nesters and suitable ground habitat is being fragmented while (quote) “flowers are being reduced to overgrown remnants surrounded by shopping malls and parking lots” or else are being planted with monoculture crops of corn or beans or canola, with no space left for the bees. One of those monoculture crops being, of course, the close-mown garden lawn.

Gardeners can mitigate the problem by leaving uncovered ground between their native plantings for bees to nest under.

Some suggested further reading about bees

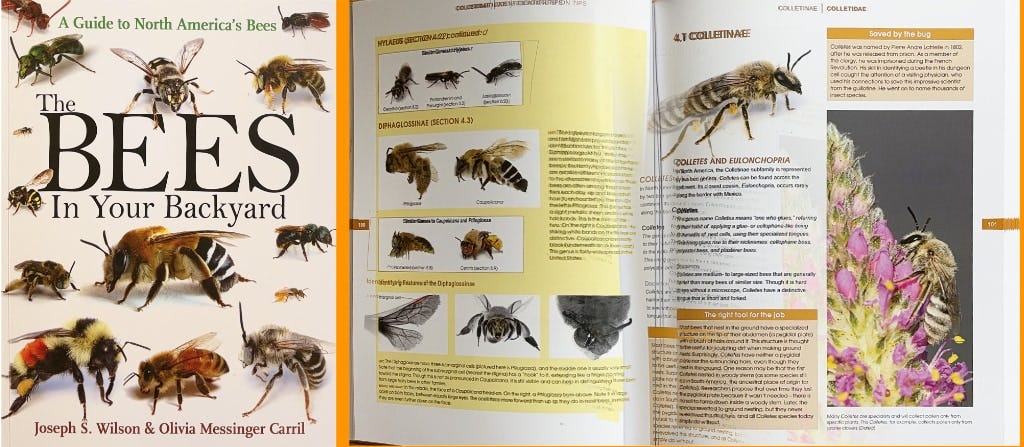

There is a splendidly detailed Guide to North American Bees published by the The Princeton Press. Fully illustrated, Honey, Bumble and Solitary Bees thoroughly covered. Written by academics but eminently readable by any interested person . Not at all expensive either …

Then there are several very enjoyable books by Dr. Dave Goulson who is a world expert on Bumble Bees and travels the planet in search of them. His books are as much travelogues as they are biology focussed. I cannot recommend them too highly. Here are the titles:

A Sting in the Tail

Silent Earth: Averting the Insect Apocalypse

The Garden Jungle: or Gardening to Save the Planet

Bee Quest

All available, as they say, from any decent book store. Available tomorrow from Amazon. Mostly available this minute from Kindle.

Earlier in the week there was a longish article in The Guardian (28 May) by Kate Bradbury who writes a lot about native plant and wildlife gardening. The whole article is worth reading - and not only for the delightful hedgehog that illustrates it - but I draw the following extract to your attention.

Gardens are human-made habitats, but they mimic the woodland edge, so they also hold on to water, slow down wind, create shade and provide food and homes for wildlife. In cities they can absorb pollution and help reduce urban temperatures. Crucially, they also link together to form vast corridors that connect other ecosystems (the woodlands, peatlands and other terrestrial systems mentioned above), enabling species to move between them, potentially giving them space to adapt to climate change. Of course, they also absorb and store carbon – in lawns, in the bark of trees, in the sludge at the bottom of garden ponds, in soil, in leaf litter and compost.

What if the solution to these (climate) problems lies, in part, in our gardens and other green spaces? Not that gardening can stop climate change, but what if gardens could connect us with the natural world, make us more aware of the destruction all around us? What if we rise up, garden by garden, park by park, balcony by balcony and do something – anything – to help a bee or a butterfly or a bird or a hedgehog? What would our world look like if more of us were tuned into the life systems that support us?

We are hurtling towards climate and biodiversity collapse at an astonishing and terrifying rate. Most of the time I’m completely overwhelmed. But I have a little garden. And everything I do and grow in it feels like a big two fingers to the world of greed and destruction, of climate change and biodiversity collapse, of big oil giants, media moguls and ineffectual governments. Gardening helps me focus on the things I can change, helps me be hopeful about the coming year. It lifts me when nothing else does.

By way of a semi-related afterword … I was just about signing off on this edition when I happened across a post about the decline of insects (so not totally unrelated to bees. Quote:

As the cute bees, moths, and butterflies (and less cute flies, wasps, mosquitoes, and ants) who make our food and flowers grow, pollinators are often the only acceptable group of insects for the nature-averse residents of a shiny new civilization (that’s us) who no longer see nor understand the value of creatures whose history on Earth stretches back 480 million years.

We cower when a wasp enters a room and is helplessly looking for a way out. In 2020, we spent $7.36 billion dollars globally on household and garden pesticides. (That was nearly one dollar for every human on the planet.) One EPA survey found that 75% of U.S. households had used at least one pesticide indoors that year. To be honest, I’m surprised that number isn’t higher.

Most of us know little about insects, other than that some sting, some visit flowers, and some enter our homes and make us uncomfortable enough to reach for broad-spectrum poisons

It’s taken from this:

Terrific! Thanks so much for this post. This yellow-faced bumblebee was in my garden yesterday.

I've come across Digger Bees, Bumblebees, Large Carpenter Bees, paper wasps, cicada-killer wasps, and mason bees in my area. We have a lot of ground bees! And I don't use pesticide or bug killers. We spray lanternflies with soapy water. I feed birds irregularly (start in cold weather and fill the feeder maybe once a week in summer) so they dine on bugs. The only bugs I kill are mosquitoes and houseflies.