This week’s “species from the famous 1001 collection” you could see today brings to you a couple of winter Sparrows … but first:

Jeremy introduced us to three birds we could probably see on any given day, and he told us about their coloring and their sounds and their habits. It was like he pulled back a curtain, because after that talk I saw birds EVERYWHERE. I could hear them in the trees, chattering happily. It wasn’t long before I put up a bird feeder and downloaded an app to help me ID the birds. “Look Sara,” I’d say, “it’s an American Goldfinch.”

“Oh, sweet, Canada …”

This week’s additions to the list of peri-urban species that devoted readers could be seeing when out and about at the beginning of February - a couple of winter-visiting sparrows:

Two sparrows that we only see in the coldest winter months when they come south to visit and to find food that keeps body and soul together, but which are reliable visitors to our gardens and parks every winter. The American Tree Sparrow and the White-throated Sparrow.

American Tree Sparrows (Spizelloides arborea) are ground-feeders, and rarely perch on feeders for their seeds, generally taking food scattered below. Only seen in the south, their breeding grounds are far, far, far to the north in the tundra … albeit tundra with a few scraggy trees that males can do their territorial singing from. They are extremely hardy birds and quite inventive in their foraging strategy … “ … they've been seen beating grass seedheads sticking up out of the snow with their wings to release seeds they can pluck from the ground.” Well worth looking out for their terracotta-coloured caps at this time of the year. Presently they are to be found close-by us.

Populations are reasonably good, but are gradually falling for all the usual reasons that bird populations fall these days.

White-throated Sparrows (Zonotrichia albicollis). Are more commonly encountered than are Tree Sparrows - made all the easier to see by their very distinctive call that (at least, in Canada) is transliterated as “Oh, sweet, Canada, Canada, Canada … “. South of the border, they are said to sing ‘Peabody’ in place of the Canada, but that just shows how cloth-eared American birders are. Hear that call in your garden or on a walk, and you know to look for them nearby.

Their head and facial markings are very distinctive, making them easy to identify at feeders or pecking on at fallen seeds beneath them. If you happen to have a stumpery or a brush pile in your garden it will provide any visiting White-throated Sparrows a place to take cover when not feeding. Most commonly seen in. Open woodland and wood/field margins or similar garden habitat.

The White-throated Sparrow comes in two colour forms: white-crowned and tan-crowned. The two forms are genetically determined, and they persist because individuals almost always mate with a bird of the opposite morph. Males of both colour types prefer females with white stripes, but both kinds of females prefer tan-striped males. White-striped birds are more aggressive than tan-striped ones, and white-striped females may be able to outcompete their tan-striped sisters for tan-striped males. (Cornell Ornithology Lab website)

The other Sparrows here, and maybe the easiest to find, are the Dark-eyed Juncos - like this fellow drinking from a waterbacth that by rights at this date should be frozen solid all the way down. Mid January to mid February are normally the coldest weeks of the year down to minus double figure temperatures, yet look at … +5C. It is simply wrong. Pleasant, but wrong.

Snowdrops Yet To Come

While we wait impatiently for the first Snowdrops to appear in our gardens, readers may find this short article about what is to come of interest. Something to whet your appetite.

Green Wildlifing and Climate Change

I think it safe to assume that most readers of these articles will be as worried as I am about greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. In the absence of major societal and economic changes (keeping the oil in the ground etc) all we can do are small, personal things and hope that in aggregate we will have an effect in getting GHGs down, even if only a bit. One reason that climate change is particularly relevant to birders and other wildlifers is talked about in the following article posted earlier this week. The writer is in the northern USA, in Duluth at the western end of the Great Lakes and only a whisker below the Canadian border … so a similar environment to that I am enjoying just outside Montreal.

And so come to Green Birding or Green Wildlifing in general. During the Covid-19 lockdown months somehow morphed into Green Wildlifing as a much closer consideration of local fauna and flora was forced upon us. It’s not a new concept - a small number of us have been doing this for many years but the popularity has grown quite a bit since lockdown.

In essence - Green Birding/Wildlifing is a handy term for trying hard to observe the creatures we live amongst without emitting greenhouse gases, without using an internal combustion engine to get to wherever they are. The idea of that going birding just by human power alone started to be talked about some 10-15 years ago. There were attempts to “organise” ptactioners, it but it seems - thank goodness - that green birders are more than happy to be loners and avoid joining clubs or being very competitive. Despite that though there have been lists of green birding achievements and individuals who have achieved some amazing things. One birder a few years ago did a Green Big Year entirely by cycling around the United States while others keep green life lists or variants on that idea.

But what’s the point? Other than a pleasant alternative way to get fit is this much more than virtue signalling or can it really have a serious effect on climate change? I would say yes, albeit we will not save the world by ourselves. When I published my book (“Green Birding” by name, what else) I did some broad-brush calculations that you may find interesting … you can get a copy from the usual sources. [LINK]

People ask are there rules? Yes and no … birders are individualists and do things their own way, but after a lot of back and forth discussion on social media, the following seemed to be acceptable to almost everyone:

You cannot ever drive a car or get on a plane. Also, no lifts from friends and no taxis.

You can walk, cycle, paddle a canoe, ride a horse.

You may (most agree, though some don’t think it’s quite right) use scheduled public transport to get to and from a route. The bus etc has to be going there anyway, with or without you. No chartering or hiring.

If you haven’t guessed already - my take-home point for everyone is that there is so much of personal and scientific value and interest that we can enjoy if we simply step outside our front doors - cultivate your personal “patch”. Quite apart from the GHG-emission avoidance raison-d’être for green birding there is the pleasure is just getting to know the wildlife neighbours. I have also found, quite serendipitously, that our friends and neighbours in the communities where we live are eager to learn what lives in their localities. Many people are interested but sometimes a bit shy about asking.

Jim Royer, a Californian Green Birder, has said:

Green birding has developed as a way to bird that does not have a negative impact on the environment. The BIGBY (Big Green Big Year) movement that developed in Quebec and has spread to other continents, was an effort to bird in a more environmentally responsible way and to encourage birding in one's local patch. This also fosters the study all of nature in the birder's local area, not just birds. It leads to a deeper appreciation of your local area and, hopefully, even preservation and restoration efforts there. In this way, green birding often leads to green naturalism and nature activism.

There are birding advantages to green birding. On a bike or on foot, birders can see and hear birds all the time, not just at stops or for fleeting moments through the windows of a speeding car. Green birders are able to stop at any time to see and study birds found en route, not just at pullouts. Consequently, more species are seen in less distance and green birding big day species totals are approaching the totals once only recorded on big days in cars, even though the distance covered in a day by bike is far less.

Next time you go out to find birds or butterflies or wildlife flowers, leave the car at home and just walk around the neighbourhood. Or take your bike a bit further. Really get to now your patch and its wild fauna and flora. Become the local expert. Make new friends along the way.

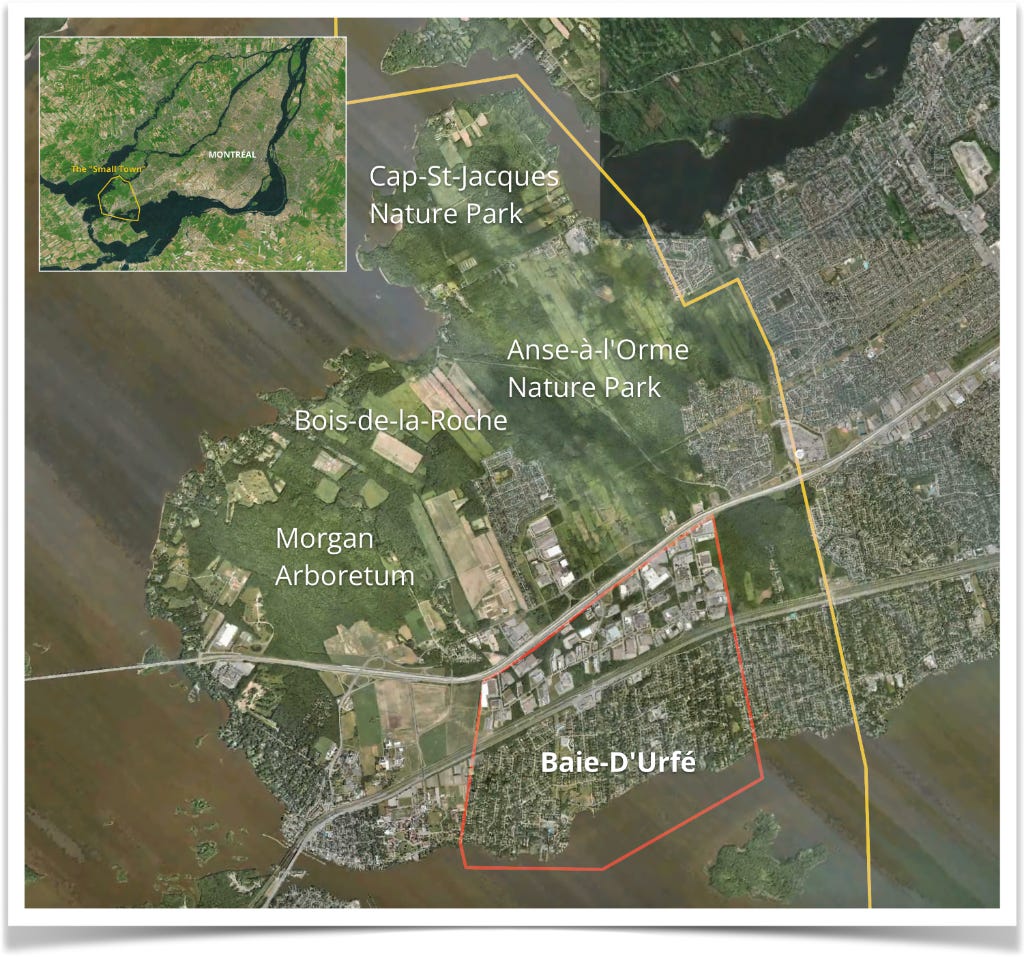

I have been asked - where is your patch, what is the area you are always learning about?

Roughly this … all accessible on foot or by bike (with a following wind). As I am not as young as I was and as I have a fully electric car, I do “cheat” though. let’s be honest 😉

** I very much hope this is not in my future …

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/first-person-ice-storm-senior-limitations-1.7107996

Richard, I don't know much about birding. So this was a thoroughly enjoyable read. A similar bird was dubbed "ping pong" bird by my kids and I'm ashamed to admit I still don't know what it's called. We just ended up calling him "Peter." Not sure why.

Love this one! We too drive our EV off to the birding spots nearby that are just too good to miss, mostly in the Skagit River delta, home to a great flyway for Snow Geese and Tundra Swans, etc. The Dark-eyed Juncos are everywhere on and beneath my feeder, with an occasional sparrow and finch breezing through. We haven’t had a flake of snow here this year, which isn’t terribly unusual, though one good hard cold snap. Thanks for the link, Richard.